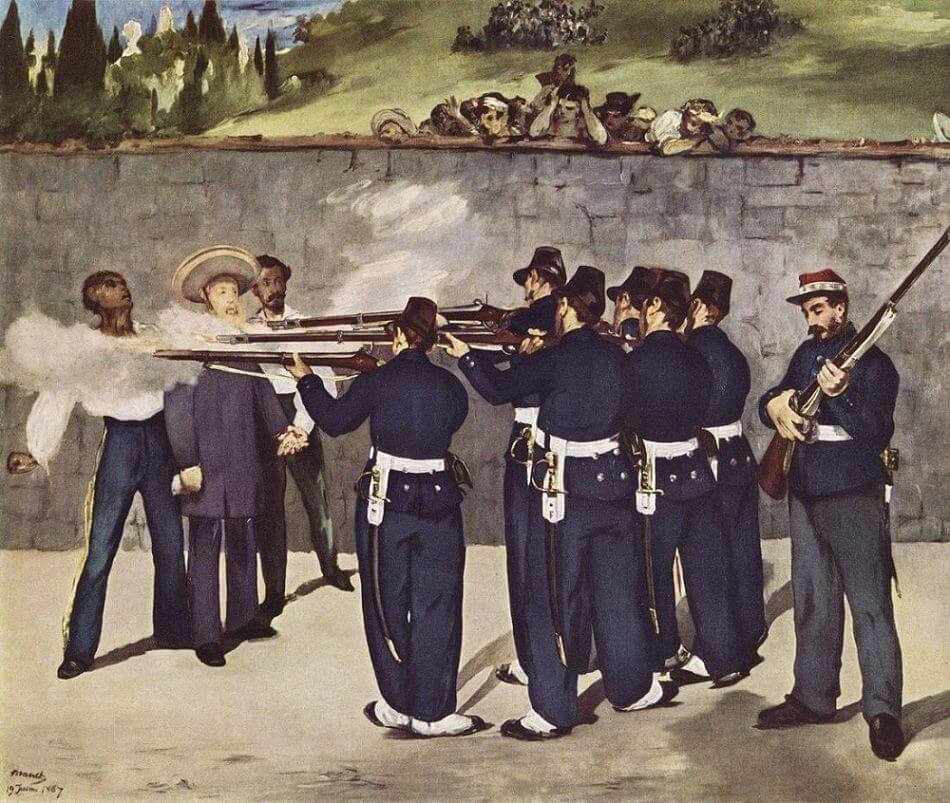

The Execution of Emperor Maximillian, 1867 by Édouard Manet

Execution of Emperor Maximilian is one of the few works in which Manet seeks a dramatic effect. The painting illustrates the climax of a well-known historical episode. Napoleon III intervened in Mexico to prevent it from gravitating toward the United States, for which he had no sympathy and which was at that time too involved in the Civil War to protest his actions effectively. French troops invaded Mexico in June 1863, and an assembly of Mexican notables proclaimed Maxirnilian - the brother of Franz Joseph of Austria - Emperor. But, once the Civil War was over, the United States demanded that the French withdraw their army, and Napoleon, in 1866, complied. Deserted by his supporters, Maximilian was captured in 1867 at Quere-taro, condemned to death, and shot in reprisal for the summary executions he himself had ordered.

This is certainly the work which shows most clearly the influence of Francisco Goya (note, for example, the rapid treatment of the people looking over the wall) and, in particular, the influence of the painting in the Prado entitled The Third of May, 1808. But there is one thing that is quite wrong according to the old school. The spectators could not be in the position in which they are shown, in view of the height of the wall, unless they were standing on scaffolding. Conscious no doubt of this faulty drawing, the artist, perhaps to disguise it, has made the fore-ground stand out sharply from the background and diverted attention from the base of the wall by showing it as little as possible between the black-trousered legs of the prisoners and the soldiers. "You can see right away that they are French," Meier-Graefe said of the soldiers. As a matter of fact, for want of Mexicans, Manet had been forced to borrow a squad from a French regiment.

In Manet's painting the soldiers have just fired (the chests of Maximilian and his two favorites are enveloped in smoke). In the back, an officer is preparing to give the coup de grace.

Neither the paintings nor a lithograph of the subject were permitted to be shown in France. As an indictment of formalized slaughter the paintings look back to Francisco Goya, and anticipate Picasso's Guernica.